Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be logged out in

Do you wish to stay logged in?

Sidney Poitier (1927-2022) was an actor, director, writer, activist and diplomat whose career spanned from the 1950s to the 2000s. His pioneering work broke racial barriers in Hollywood and redefined representation on screen.

Born in Miami to Bahamian parents, Poitier initially struggled to break into acting owing to his Bahamian accent. However, his perseverance led him to train at the American Negro Theatre in Harlem, where he honed his craft. His breakthrough role came in No Way Out (1950), where he portrayed a Black doctor who faces racism while treating a white prisoner. The film had a troubled preproduction and was even initially banned for its depiction of a race riot. As Ryan De Rosa writes in this chapter of Poitier Revisited, 'No Way Out, a film that inspired opposing responses, placed in relief the ideological battle over the meaning of race relations on film and outside film.'

Poitier's career in the 1950s and 1960s was marked by groundbreaking achievements. His performance in The Defiant Ones (1958) earned him his first Academy Award nomination. In 1963, he became the first Black actor to win the Academy Award for Best Actor for his role in Lilies of the Field, symbolising progress in what continued to be a deeply segregated industry. Testament to the significance of his win was that he remained the only Black actor to be recognised for a leading role until Denzel Washington's win in 2001 for Training Day. In accepting his award, Washington paid tribute to Poitier, as Cynthia Baron notes in this chapter of Denzel Washington, he concluded his speech by saying "I'll always be following in your footsteps; there's nothing I would rather do, sir."

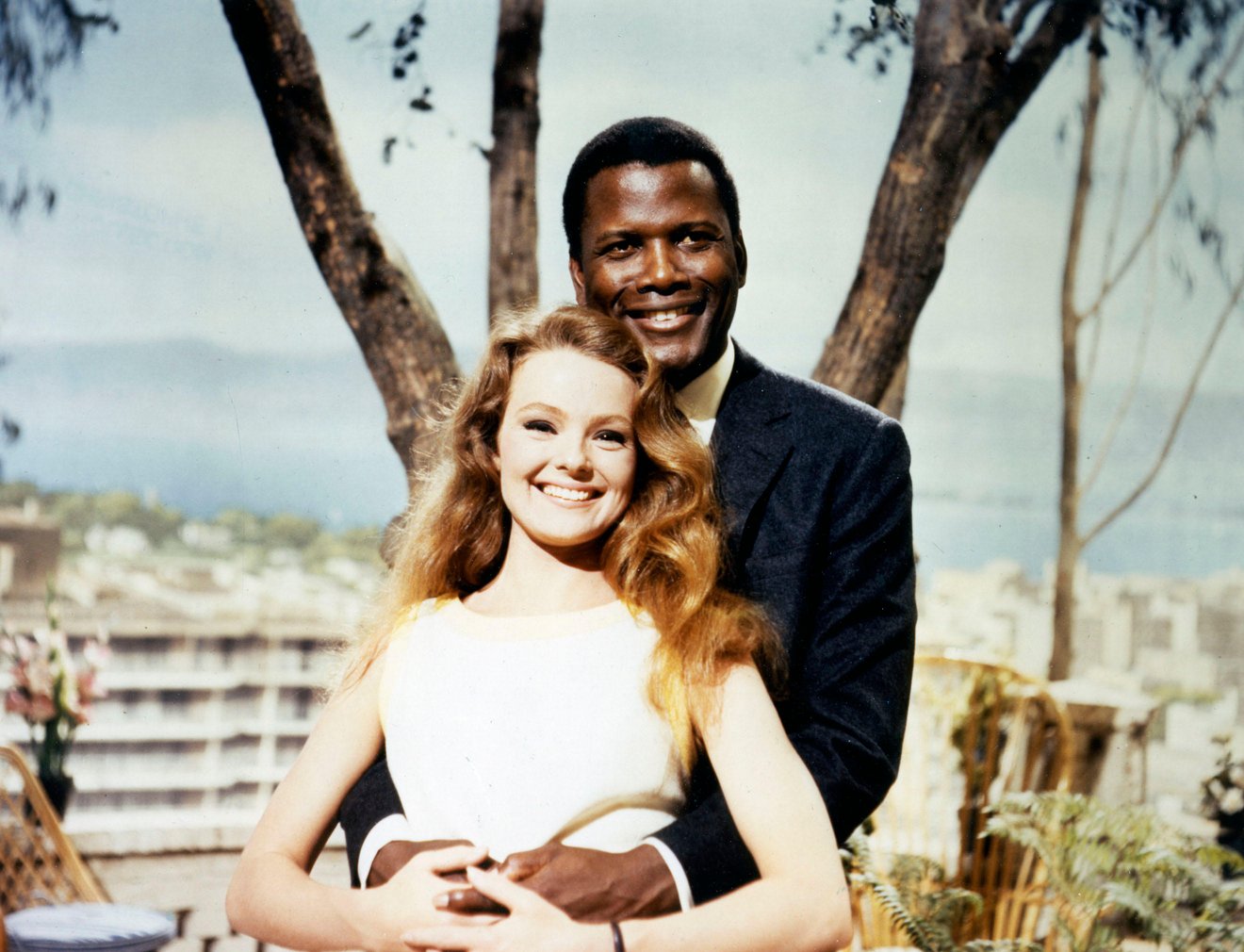

In perhaps his best known film, Guess Who's Coming to Dinner (1967), Poitier tackled the sensitive subject of interracial marriage and racism, playing a highly educated and accomplished physician. As Ruth Doughty writes in this chapter of Sound and Music in Film and Visual Media, 'It is fair to say that Poitier was very much the integrationist hero. He constantly played the middle-class, conservative, non-sexual acceptable face of black America. Poitier worked to give the African American community noble black heroes.'

That same year, in In the Heat of the Night, he portrayed Virgil Tibbs, a Black detective from Philadelphia investigating a murder in the racially tense Southern town of Sparta. The film famously featured the radical scene where upon being slapped by the white plantation owner Endicott, Lt. Tibbs slaps him back. While on the one hand the film was celebrated for its rejection of stereotypes, as Cary Edwards writes in this chapter of The Vigilante Thriller, 'The traditional opposition of white as normal and Black as other was consciously subverted in this film in which Tibbs is shown to be a highly moral and sophisticated figure as opposed to the ignorant, racist townspeople.' It was also met with criticism, because, as Paul Kerr writes in this chapter of Hollywood Independent, 'the extent to which white liberal tolerance of Poitier as the acceptable face of African Americans explained the actor’s appeal, as the exception that proves the racist rule, it remained controversial.'

The constraints of being an isolated Black creative in overwhelmingly white production contexts inspired Poitier to expand his influence by stepping behind the camera. As Keith Corson writes in this chapter of Poitier Revisited, 'Directing, one would believe by reading between the lines of Poitier's statements (and omissions), was largely a tool for control in Hollywood, and not a creative enterprise on par with acting.' His directorial debut, Buck and the Preacher (1972), was a Western that featured a predominantly Black cast, showcasing stories outside the usual stereotypes. The film was part of the post 1971 Blaxploitation film boom, as described by Lee Broughton in this chapter of The Euro-Western, 'these American Westerns featured a new breed of black gunfighters...they were assertive and independent and fully able to shoot and kill white enemies.’ He completed nine films as a director, including the successful comedies Uptown Saturday Night (1974) and Stir Crazy (1980).

Sidney Poitier inspired generations of actors, directors, and writers of colour and his achievements were recognised with numerous honours, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009. His unrelenting advocacy for equality made him a cultural icon whose performances continue to resonate with contemporary audiences.

Homepage banner: Sidney Poitier. Image courtesy of Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo.